New Houlka, Mississippi

New Houlka, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

Walker Street | |

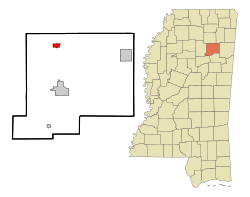

Location of New Houlka, Mississippi | |

| Coordinates: 34°2′11″N 89°1′12″W / 34.03639°N 89.02000°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Chickasaw |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.23 sq mi (3.18 km2) |

| • Land | 1.23 sq mi (3.18 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 698 |

| • Density | 568.40/sq mi (219.50/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 38850[2] |

| Area code | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-51420 |

| GNIS feature ID | 671516[3] |

New Houlka (/ˈhʌlkə/), also referred to simply as Houlka, is a town in Chickasaw County, Mississippi, United States. It was founded in 1904 to take advantage of a railway line of the Gulf and Ship Island Railroad. Residents moved their buildings over from the original settlement, now referred to as "Old Houlka", located to the west. The population was 626 at the 2010 census.

Started around a fur trading post prior to 1794, Old Houlka is the oldest surviving settlement in north Mississippi.[4] In the 19th century, much of the land was developed for cotton plantations and the market town did good business.

History

[edit]This area was a well-established center of Chickasaw culture by the 1500s.[5]

Settlers arrived in the late 1700s and established a Chickasaw Agency House at Houlka for trading with the natives.[5] Agency representatives called the settlement "Holkey" in their earliest correspondence, which dates from 1794 after the United States gained independence from Great Britain.[4]

Houlka was located at the crossroads of the ancient Native American pathways known as the Natchez Trace and the Gaines Trace.[6]

In 1805, Silas Dinsmoor hosted a ball at the Agency House. Attending were future U.S. Representative John McKee and former U.S. Vice-President Aaron Burr.[7] A post office was established in 1826.[4] The cultivation and processing of cotton became the basis of the economy, and African slaves were brought to the region through the domestic slave trade to serve as laborers. The production of cotton brought some wealth to white planters.

During the Civil War, Confederate forces led by General Samuel J. Gholson clashed with Federal troops at a swamp-crossing near Houlka.[8]

Houlka was incorporated in 1884.[6] Houlka High School was founded in 1890 "to establish a permanent and high grade institution for the education of white students of both sexes".: 578 [9] The Legislature also prohibited sales of "intoxicating liquors" within 4 mi (6.4 km) of the school.[9] That year the Mississippi legislature, dominated by white Democrats, passed a new constitution that effectively disenfranchised most blacks, a status that the state maintained well into the 1960s to exclude them from the state's political system.

In 1904, the Gulf and Ship Island Railroad built a line from New Albany to Pontotoc, passing 1 mi (1.6 km) east of Houlka. Soon after, residents began moving to "New Houlka", located near the railway line, which had become critical to commerce. Buildings were rolled on logs from Old Houlka to New Houlka, and pulled by teams of oxen.

By 1906, New Houlka had a bank, three churches, a saw mill, an academy, a plow factory, and a population of about 500. The town was incorporated that same year.[5][6][10][11]

During the mid to late 20th century, railroads restructured and closed many lines, even for freight, because of competition from trucking. In 2004, the railway running through New Houlka, by then owned by the Mississippi Tennessee Railroad, was abandoned between New Albany and Houston, a distance of 43.2 mi (69.5 km). Under the federal 'Rails to Trails' program overseen by the ICC, the track was removed and a rail trail called the "Tanglefoot Trail" was built on the right-of-way, creating a new recreational and public health resource.[12]

Name

[edit]The etymology of Houlka is unclear. Some hold it is derived from a Native American name meaning "low land" or "low water," while others believe it means "turkey".[13]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 1.2 square miles (3.2 km2), all land.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 646 | — | |

| 1980 | 710 | 9.9% | |

| 1990 | 558 | −21.4% | |

| 2000 | 710 | 27.2% | |

| 2010 | 626 | −11.8% | |

| 2020 | 698 | 11.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

As of the census[15] of 2000, there were 710 people, 285 households, and 186 families residing in the town. The population density was 581.7 inhabitants per square mile (224.6/km2). There were 319 housing units at an average density of 261.3 per square mile (100.9/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 74.23% White, 24.79% African American, 0.56% from other races, and 0.42% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.97% of the population.

There were 285 households, out of which 34.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.5% were married couples living together, 18.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.7% were non-families. 31.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 17.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.49 and the average family size was 3.16.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 29.4% under the age of 18, 7.9% from 18 to 24, 28.9% from 25 to 44, 19.3% from 45 to 64, and 14.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females there were 88.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 80.9 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $20,417, and the median income for a family was $28,958. Males had a median income of $22,353 versus $18,542 for females. The per capita income for the town was $10,812. About 20.0% of families and 24.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 29.7% of those under age 18 and 26.4% of those age 65 or over.

Education

[edit]The Town of New Houlka is served by the Chickasaw County School District. It is the location of the Houlka Attendance Center. The old Houlka High School building is still extant.

Notable people

[edit]- Charles Easley, Associate Justice of the Mississippi Supreme Court[16]

- Earl J. Hamilton, historian[17]

- Jim Hood, Former Mississippi Attorney General[18]

References

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Houlka ZIP Code". zipdatamaps.com. 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Houlka

- ^ a b c Atkinson, James R. (2004). Splendid Land, Splendid People: The Chickasaw Indians to Removal. University of Alabama Press. p. 142. ISBN 9780817350338.

- ^ a b c Mississippi: The WPA Guide to the Magnolia State. Viking Press. 1938. p. 462. ISBN 9781604732894.

- ^ a b c Young Turner, Debbie (September 29, 2012). "Houlka, Miss.: 'Center of the Universe'". WN.com.

- ^ Kennedy, Roger G. (1999). Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson: A Study in Character. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199923793.

- ^ Foster, Buck T. (2006). Sherman's Mississippi Campaign. University of Alabama Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780817315191.

- ^ a b Mississippi Session Laws. Mississippi Legislature. 1890. pp. 578, 579.

- ^ "Interpreting the Trail". Rails-to-Trails Recreational District. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ Rowland, Dunbar (1907). Mississippi: Comprising Sketches of Counties, Towns, Events, Institutions, and Persons, Arranged in Cyclopedic Form. Vol. 1. Southern Historical Publishing Association. p. 890.

- ^ Howe, Tony. "(New) Houlka, Mississippi". Mississippi Rails. Retrieved May 23, 2015.

- ^ Baca, Keith A. (2007). Native American Place Names in Mississippi. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-60473-483-6.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Brumfield, Patsy R. (January 14, 2009). "State's Supreme Court Races Cost Nearly $1M". Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal.

- ^ "Earl Jefferson Hamilton". Asociación Española de Historia Económica. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ^ Lehrer, Eli (December 15, 2014). "Revealed: Little-Known Mississippi Attorney General Go-To Man for Hollywood". Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014.